Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973) is considered the most prolific engraver of the 20th century, having created over 2,400 prints over his lifetime, out of which 197 are linocuts. The artist pushed the technical and artistic possibilities of linocut, a medium typically associated with commercial printing and education, to their limits. By revealing its refinement and subtleties, Picasso affirmed the medium as an art form in its own right.

The linocuts shown here have been selected not only to illustrate Pablo Picasso’s journey in linocut, but also for their rarity. The majority exists only in one or a few impressions, and the list of works at the end has been chronologically organised so as to create a visual map of Picasso’s linocut adventure.

-

At the beginning of this adventure, from 1955 to 1958, Picasso conceived subjects created from a single cut on linoleum - a relatively simple technique - printed in one colour, usually black or brown. These powerful compositions all bear traces of the artist mastering a new material. They resemble German Expressionist works, and we are fortunate to be able to offer wonderful examples of these early subjects such as the two states of Grand nu debout and Femmes à leur Toilette. As well as the beautiful Profil de Jacqueline I, II, III, IV that Anne-Françoise Gavanon, one of our directors discusses in the video below. We have tried to make it as if you were on our stand - no sleek filming, just the linocut, you and Anne-Françoise.

-

-

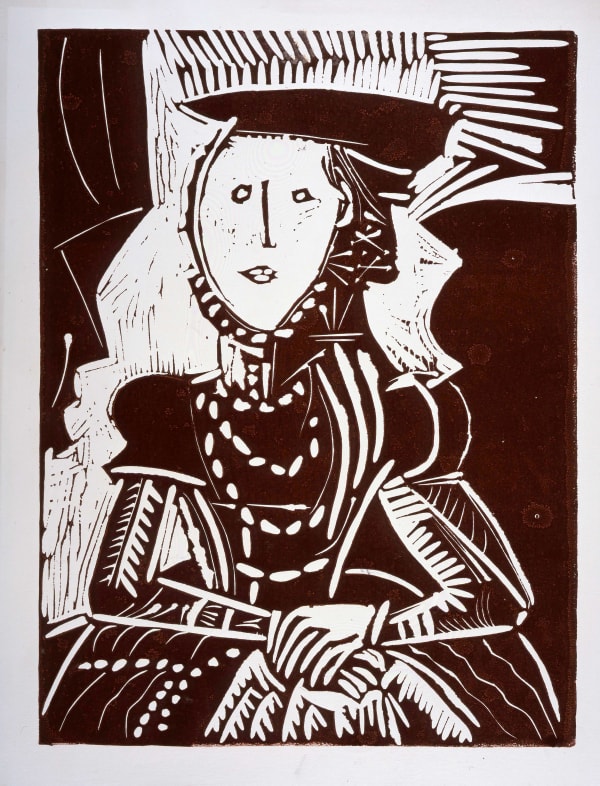

We then have the privilege to offer an impression of the black plate of Portrait de jeune Fille, d'après Cranach le Jeune. II made on 4 July 1958. This subject is the most sought-after linocut by Picasso. This linocut subject was inspired by Portrait of a young Lady, a 1564 panel by Cranach le Jeune in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Picasso never went to Austria but was sent a postcard of the panel by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, his dealer, which triggered his creativity. The artist’s re-interpretation of Cranach’s panel is equally faithful and personal, and is a technical tour de force in interpreting the art of the Renaissance. Alongside the image of the black plate impression, you will find a photograph of the finished image as well as a reproduction of the Cranach panel - just click on the black plate to see the other two.

The title bears the Roman number ‘II’ giving a clue to the possibility of a preceding subject. Indeed, the day before, Picasso had made a first attempt at interpreting the panel. Of this very little known first ‘Cranach’, only four impressions are recorded, and we are able to offer an impression printed in a warm brown.

-

Although Portrait de jeune Fille, d'après Cranach le Jeune. II is the most sought-after linocut by Picasso, the artist found the process of making it quite tedious. It consequently spurred him to work with what has come to be called the reductive technique. Contrary to what is recorded in most of the literature, the artist did not invent the reductive technique, but learned it from his young linocut printer, Hidalgo Arnéra, from the archives of whom many of our impressions come, an impeccable provenance.

The reductive technique, as developed by Picasso with the help of Arnéra, means that more than one state can be printed from a single linocut block with a separate colour for each state. A single linocut plate is cut and then printed (1st state), and then if necessary cut some more (2nd state) and printed again in another colour on top of the impressions of the first state. The more colours the artist desires, the more stages of cutting and printing the plate goes through; each time, the amount of raised surface area available to take the ink is reduced. Where several states are involved, by the time the image is complete there is usually very little raised linoleum left on the block, hence the name of the technique.

-

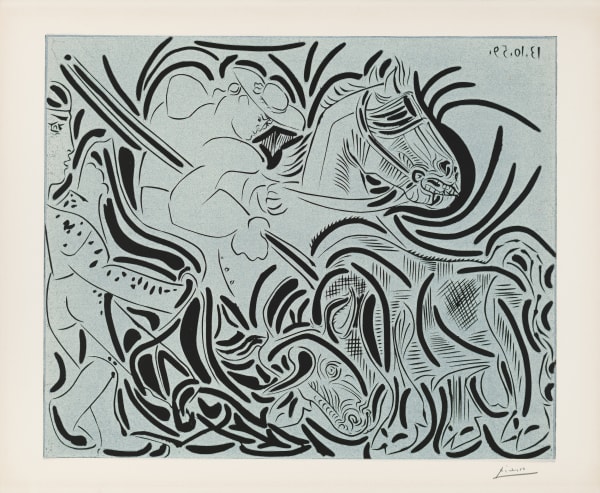

Pablo Picasso

Le Banderillero

Linocuts printed in colours, 1959

52.5 x 63.8 cm

-

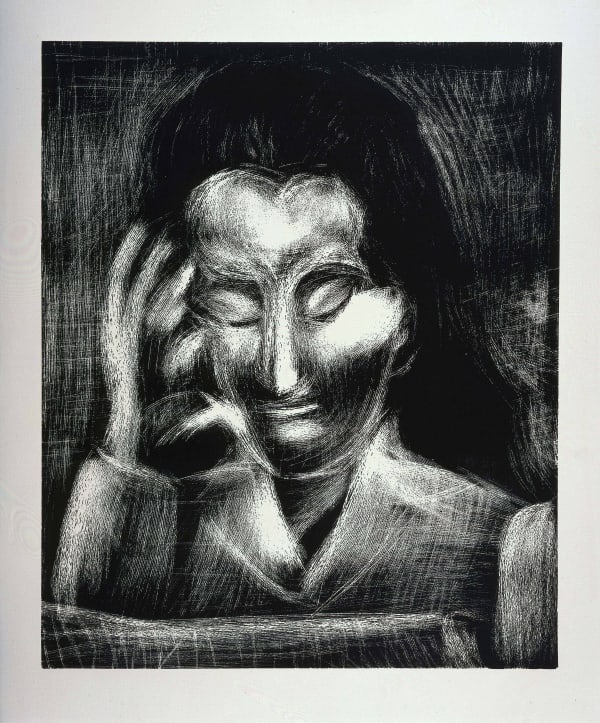

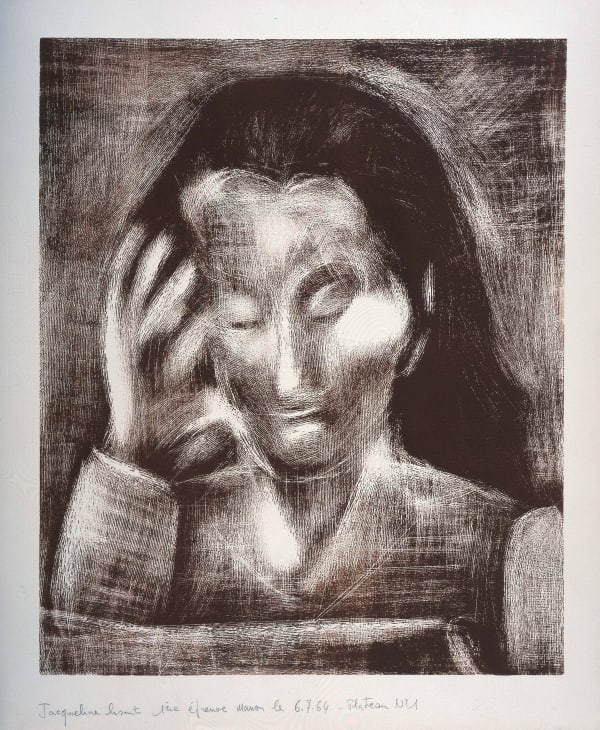

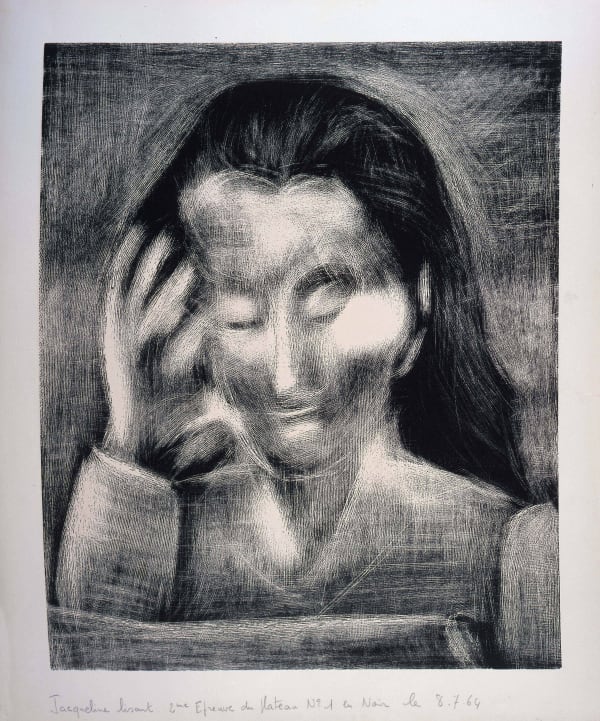

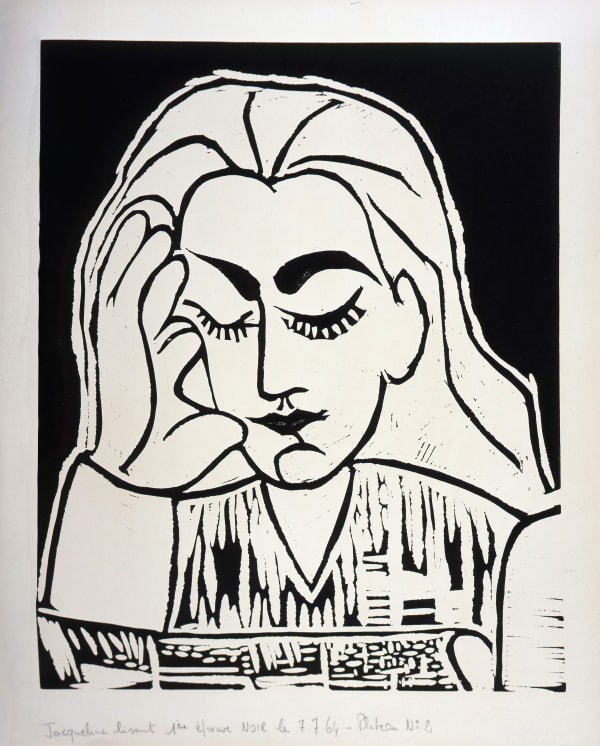

Finally, Jacqueline lisant of 1962 - one of our favourites of all Picasso linocuts. This set of five impressions illustrates a turning point for the artist; he decides to represent relief and volumes in linoleum, a material that lends itself to flatness. Using a grattoir, Picasso produced a crosshatching effect, directly inspired by the intaglio technique, giving a sculptural dimension to his composition. Picasso used two blocks, one for the sculpted rendition of the subject, which is all delicacy and finesse, the other for the strong and simplified outlines of the figure as shown here. Picasso finally asks his printer to print the outline block over the modelling block. Et voilà a completed image!

We hope you have enjoyed this brief tour of Picasso’s journey in linocut, and please do feel free to contact us to discuss further.